Tales from Tour Guides: the stories that fascinate, perplex and inspire the Tour Guides of Peterborough Cathedral, written during lockdown.

The West Front, Pope Innocent III and King John

By Norman Tregaskis

The Normans began building Peterborough Abbey Church in 1118 and, progressing westwards, reached the inner west wall in the 1190s (for simplicity, let’s say 1198, taking 80 years in round figures).

The Normans began building Peterborough Abbey Church in 1118 and, progressing westwards, reached the inner west wall in the 1190s (for simplicity, let’s say 1198, taking 80 years in round figures).

Completed in 1238 (without the porch), the West Front took another 40 years – half the time taken to build the main body of the church.

Why so unbelievably long?

According to Jonathan Foyle*, the West Front had risen to just above the three arches by about 1208 (10 years), yet the gables, gable rooves and the tower tops took 30 years more. What happened? Coincidentally, in March 1208 during a row with King John, Pope Innocent III placed an Interdict upon England, forbidding church services countrywide. This act, and King John’s response, had profound effects upon the population and the Church, and stopped construction. Perhaps understanding the Interdict, its consequences and the main actors will help to explain the West Front hiatus.

Pope Innocent III, from a fresco at Sacro Speco. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Pope Innocent III was enthroned in 1198, and in his maiden speech, set out his stall by describing himself thus:

“See therefore what kind of servant he is who commands the whole family. He is the Vicar of Jesus Christ, the successor of Peter … he is the mediator between God and man, less than God, greater than man”.

Previously, all Popes had been called ‘the Vicar of Peter’ but, by appointing himself Vicar of Christ, Innocent declared his authority as supreme over the rulers of the Christian world.

John was the youngest of King Henry II’s four sons. His instinctive lust for power was thwarted by being lowest on the succession ladder and lacking prospective inheritance. This left him resentful and volatile. Chroniclers described him as having “distasteful – even dangerous – personality traits, such as pettiness, spitefulness and cruelty”; another said “he had the mental abilities of a great king but the inclinations of a petty tyrant”. However, family rebellion and the deaths of King Henry II and two of his sons advanced Richard to King and John to Heir Apparent. On Richard I’s death in 1199, John was finally King.

King John. Dulwich Picture Gallery. Source: Wikimedia Commons

By 1202 John had lost his inherited empire in northern France, and consequently held no love for anything French. Therefore in 1206, when Innocent III consecrated a Parisian theology lecturer, Stephen Langton, as Archbishop of Canterbury, John would have none of it. Precedent set the Archbishop as the King’s chosen ecclesiastical representative to the Pope, whereas Innocent saw the Archbishop as his man, his channel of authority over the King. Innocent pushed. John was immovable. Therefore, Innocent invoked the Interdict in 1208 and excommunicated John – who remained intransigent.

Under the Interdict, bishops could not permit church services except for baptisms and penance of the dying. Excluded were celebrations of mass, and all marriage and burial services. The Interdict therefore deprived the people of spiritual consolation, and was intended to make the population hostile to the King. It was a political weapon, and for John it was a declaration of war.

Caught between disobeying either the King or the Pope, many monks and clergy fled the country, but could not escape John’s reach. He confiscated the property of ‘deserters’, and with characteristic cruel humour, had the illicit wives and paramours of supposedly celibate churchmen arrested and expensively ransomed. Indeed, most of John’s measures were economic because he needed money for his struggle to recover lost French lands. Therefore from 1208, John’s main thrust was seizure of abbey and church revenues. Peterborough Abbey was now without income and poor, and West Front construction stopped.

The Interdict accounts for only six years of stoppage to 1214, but its consequences also caused great delay:

- Medieval stone masons tended to be itinerant, and it would have taken time to re-engage the numbers who had moved on in 1208.

- After restoration of estate revenues, the achievement of usable cash flow probably took at least two harvests.

- Spanning those early harvests, the trickling revenue was surely too little for an immediate large-scale restart on the West Front, but enough, perhaps, for the new abbot, Robert of Lindsey, to begin his passion to gradually enlarge and glaze 30 church and 14 cloister windows. Thereby, he diverted resources from the West Front, adding significant delay – probably years.

- Five abbots spanned the 40 years of West Front construction, doubtless each having his say about design changes, and counter changes – some requiring the dismantling of earlier stonework. Without the Interdict there might have been fewer abbots and fewer redesigns – meaning years saved.

Although the delays consequent upon the Interdict can be reasonably supposed, the total amount of delay can only be conjectured, perhaps 14 years? That would leave a feasible 16 years to complete the West Front. If so, the arithmetic to explain 40 years taken to build the West Front could be:

10 years to the top of the arches + 14 years delay + 16 years of work to complete

= 40 years.

This sum seems reasonable even if, by their vanity and obstinacy (dare I say pride and prejudice?), the King and the Pope were not.

The completed West Front of Peterborough Cathedral

* Jonathan Foyle’s architectural history, Peterborough Cathedral: A Glimpse of Heaven, is available here: https://www.ticketisland.co.uk/ticketi_slpos_product?bi=PeterboroughCathedral&pid=47.

If you are able to make a donation towards the cost of maintaining this beautiful and historic cathedral, it would help us a great deal. You can do so via the Cathedral’s Virgin Money Giving page. Thank you.

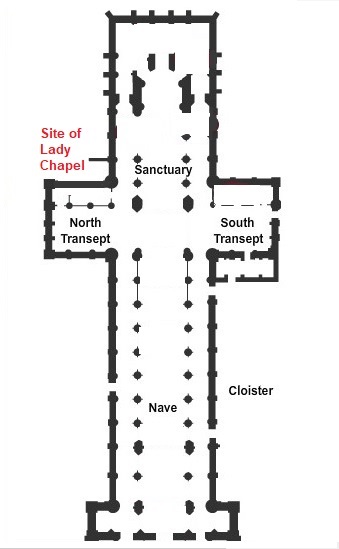

These may be seen from a distance by anyone standing in the eastern half of the Nave, but to appreciate them in detail, you have to take a

These may be seen from a distance by anyone standing in the eastern half of the Nave, but to appreciate them in detail, you have to take a